From the book Poverty of Spirit by Johannes Baptist Metz

To become human as Christ did is to practice poverty of spirit, to obediently accept our innate poverty as human beings. This acceptance can take place in many of life's circumstances where the very possibility of being human is challenged and open to question. The inevitable summons to surrender to the truth of our Being suggests itself in many ways. Here we want to highlight the most important forms that our poverty takes, to show how our daily experiences point us toward the desert wastes of poverty.

Poverty of the commonplace

There is the poverty of the average person's life, whose life goes unnoticed by the world. It is the poverty of the commonplace. There is nothing heroic about it; it is the poverty of the common lot, devoid of ecstasy.

Jesus was poor in this way. He was no model figure for humanists, no great artist or statesman, no diffident genius. He was a frighteningly simple man, whose only talent was to do good. His one great passion in his life was his "Abba." Yet it was precisely in this way that he deomonstraed "the wonder of empty hands" (Bernanos), the great potential of the person on the street, whose radical dependence on God is not different from anyone else's. Such a person has no talent but that of one's own heart, no contribution to make except self-abandonment, no consolation save God alone.

Poverty of neediness

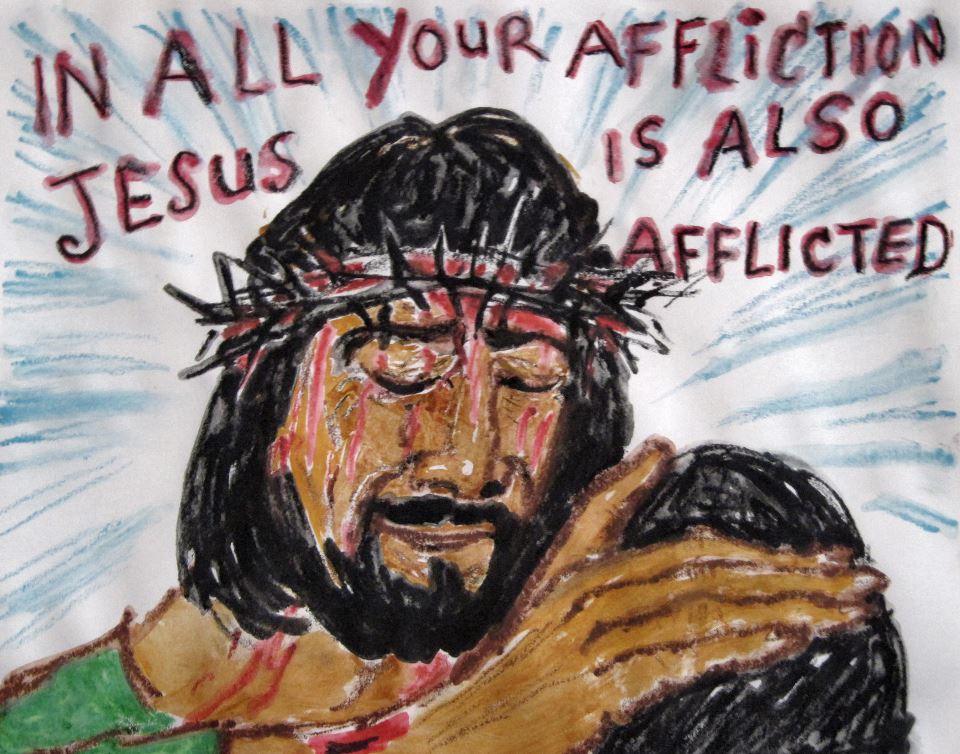

Related to this poverty is the poverty of misery and neediness. Jesus was no stranger to this poverty either. He was a beggar, knocking on people's doors. He knew hunger, exile and the loneliness of the outcast (so much that he will judge us on these things). He had no place to lay his head, not even in death-- except a gibbet on which to stretch his body.

Christ did not "identify" with misery or "choose" it; it was his lot. That is the only way we really taste misery, for it has its own inscrutable laws. His life tells us that such neediness can become a blessed sacrament of "poverty of spirit." With nothing of one's own to provide security, the wretched person has only hope-- the virtue so quickly misunderstood by the secure and the rich. The latter confuse it with shallow optimism and a childish trust in life, whereas hope emerges in the shattering experience of living "despite all hope". We really hope when we no longer have anything of our own. Any possession or personal strength tempts us to a vain self-reliance, just as material wealth easily becomes a temptation to "spiritual opulence."

To become human as Christ did is to practice poverty of spirit, to obediently accept our innate poverty as human beings. This acceptance can take place in many of life's circumstances where the very possibility of being human is challenged and open to question. The inevitable summons to surrender to the truth of our Being suggests itself in many ways. Here we want to highlight the most important forms that our poverty takes, to show how our daily experiences point us toward the desert wastes of poverty.

Poverty of the commonplace

There is the poverty of the average person's life, whose life goes unnoticed by the world. It is the poverty of the commonplace. There is nothing heroic about it; it is the poverty of the common lot, devoid of ecstasy.

Jesus was poor in this way. He was no model figure for humanists, no great artist or statesman, no diffident genius. He was a frighteningly simple man, whose only talent was to do good. His one great passion in his life was his "Abba." Yet it was precisely in this way that he deomonstraed "the wonder of empty hands" (Bernanos), the great potential of the person on the street, whose radical dependence on God is not different from anyone else's. Such a person has no talent but that of one's own heart, no contribution to make except self-abandonment, no consolation save God alone.

Poverty of neediness

Related to this poverty is the poverty of misery and neediness. Jesus was no stranger to this poverty either. He was a beggar, knocking on people's doors. He knew hunger, exile and the loneliness of the outcast (so much that he will judge us on these things). He had no place to lay his head, not even in death-- except a gibbet on which to stretch his body.

Christ did not "identify" with misery or "choose" it; it was his lot. That is the only way we really taste misery, for it has its own inscrutable laws. His life tells us that such neediness can become a blessed sacrament of "poverty of spirit." With nothing of one's own to provide security, the wretched person has only hope-- the virtue so quickly misunderstood by the secure and the rich. The latter confuse it with shallow optimism and a childish trust in life, whereas hope emerges in the shattering experience of living "despite all hope". We really hope when we no longer have anything of our own. Any possession or personal strength tempts us to a vain self-reliance, just as material wealth easily becomes a temptation to "spiritual opulence."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please no spam, ads or inappropriate language.